[Profile] Benjamin Landais, Senior Lecturer in Modern History - February 2020

My main field of research is Central and Balkan Europe from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, which I have studied from different perspectives: manifestations of ethnicity before the birth of nationalism, controls on peasant mobilities and colonisations, political and infrapolitical practices in the village, and social uses of rural cartography. These themes have in common that they participate in the construction of a history from below of this Ancien Régime society, situated on the margins of the Europe of the Enlightenment.

- The edition of a corpus of letters (in French, German and Italian) which deal with the management of the Austro-Ottoman border in the middle of the 18th century and which show the complexity of the relationships established between the micro-actors (makeshift spies, improvised interpreters, migrant smugglers and junior officers) of a daily diplomacy.

- The organisation of an international colloquium in Avignon (end of May 2020) on rural parcel maps in modern Europe, documents that have long been unjustly disregarded by research in history and geography.

- In connection with an important collective experience in the recent history of the Vaucluse, I am collaborating on the translation and publication of a Romanian book on the journey of the "Banatais" of La-Roque-sur-Pernes by Éditions Universitaires d'Avignon.

Why did you choose to work in academic research?

Originally - and this is still the case, despite the deterioration of the conditions in which the profession is practised - my choice was guided by two elements: the taste for investigation and discovery, on the one hand, and the relative freedom and independence of the researcher, on the other. In other words, to be able to point out the gaps in the dominant stories and help fill them. I also appreciate the absence of jargon in the writing of this discipline, as well as the numerous bridges it allows to build towards other fields (geography, economics and anthropology among others).

What advice would you give to students who want to do research?

Research, in history perhaps more than anywhere else, is often solitary. It is essential to test the strength of one's motivation before embarking on a multi-year project. It is also essential to discover and cultivate a vocation for teaching, which I believe cannot be dissociated from research activity. Finally, we need to be aware of the precarious economic situation and the limited opportunities that await young researchers. This bleak future can only be changed if we put a stop to the deleterious policies decided at national and European level, as shown by the current mobilisation against the LPPR (Loi de Programmation Pluriannuelle de la Recherche).

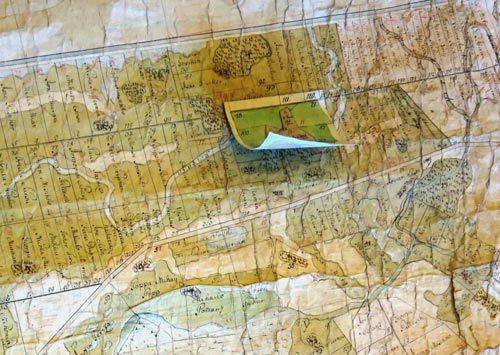

Which object or image from your research best illustrates you?

A cartographic "patch", pasted on the cadastral plan of a Romanian-speaking village at the end of the 18th century. A rare material testimony that shows us the document in the process of being made (or unmade...).

Mis à jour le 26 October 2023