[Portrait] Claire Balandier, Senior Lecturer in Ancient History

What is your research about?

My research focuses on the geopolitical history of Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus, Syria-Phoenicia) from the late classical period (4th century BC) to the High Roman Empire (2nd century AD) through the study of ancient cities and their defensive policies. These regions have always been the object of covetousness because of their geostrategic importance, which is still reflected in contemporary conflicts. I study the way in which an allogeneous power, whether Persian, Greco-Macedonian or Roman, establishes itself on a territory and takes control of it by founding cities, ports and building fortified networks.

What are your current scientific activities?

The archaeological cooperation initiated 3 years ago with the University of Warsaw to excavate and study the remains of a temple and underground cult chambers in Paphos is entering its final year: after our last two excavation campaigns on these monuments in November and May, the programme will end next September [2022] with a round-table discussion at the Franco-Polish scientific centre in Paris.

This programme will be followed by another European collaboration project, with the University and the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus: the French School of Athens has selected our study project of the urban enclosure of Nea Paphos for its next five-year research programme (2022-2026).

I am also preparing, in collaboration with a colleague from the University of Sydney, the 3rd international colloquium on Paphos which will be held at the French School of Athens at the end of 2022 (the 1st colloquium on Paphos was held in Avignon in 2012).

Upcoming publications this year: the proceedings of the 2nd Paphos ColloquiumI am co-editor with two colleagues from the University and the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus, and a monograph on the urban area of AmathonteAnother Cypriot city, co-authored with Pierre Aupert, is in press at the Ecole française d'Athènes and finally the preparation of the first volume of the discoveries of the French Archaeological Mission in Paphos.

Why did you choose to work in academic research?

I wanted to become a teacher and I have been fascinated by History since childhood, fascinated by the traces of the past, whether it be prehistoric caves, Greco-Roman amphorae, Cathar castles or Assignats from the Revolution...

I also loved languages, ancient and modern, which is necessary for research.

At university, my interest in antiquity and especially in research was confirmed, especially as, in parallel with my history studies, I trained in archaeology in the field in France but also in Russia, Greece, Cyprus, Syria, Palestine, Albania... Becoming a researcher in antiquity became a matter of courseThe aim of the project is to link the study of written sources with material sources, but also the sensitive discovery of the places studied, because if research in History leads us to travel back and forth between the present and the past, it also leads us to travel in space and to discover other places, other people, other ways of seeing.

As for the University, it was another obvious fact: even if the time we can devote to our research is shrinking, with the increase in our teaching and administrative tasks and the search for funding, linking research and teaching still seems to me to be necessary in order not to shut oneself up in one's scientific bubble, to keep a certain distance, and above all to pass on to students what I myself have received from my elders in the classroom or in the field. This handing over, which is sometimes done happily, from the bachelor's degree to the doctorate, is probably the most gratifying aspect of our public service mission because it also contributes to training our future colleagues, teachers, researchers or enlightened fellow citizens.

What advice would you give to students who want to do research?

It is very difficult to make research your profession because there are few jobs, especially in the humanities, you have to be aware of this, but it is not new... However, if research is a real passion and you are determined, very hard-working, and enjoy teamwork as much as thinking and writing alone, you must not be discouraged, persevere without closing any doors, do not hesitate to go and see elsewhere (Solon of Athens, one of the seven Greek sages, quite rightly said that travel trains youth) and know that research is also a state of mind... If it requires rigour and often creates frustration, it also brings a lot of satisfaction.

So don't turn away from research if that is your profound choice If you don't succeed, you will have enjoyed yourself and been enriched, and you will continue to look at the world with curiosity, critical thinking and humanism... You will not have wasted your time!

Which object or image(s) from your business best illustrate(s) you?

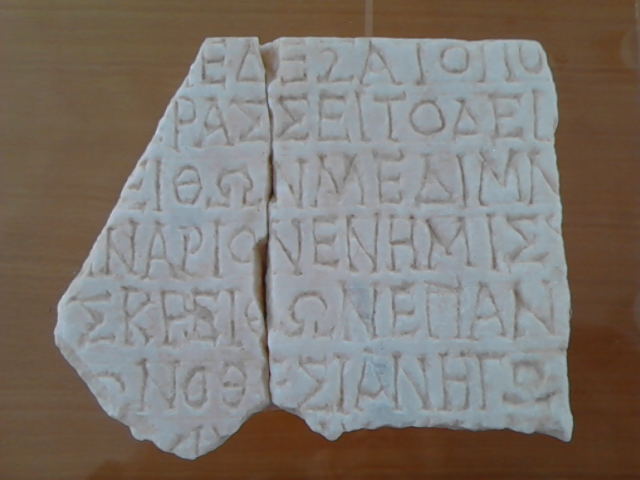

These fragments of a Greek inscription from the Roman periodThese objects, discovered during excavations in 2016 in Paphos by history students from the University of Avignon, illustrate the immense puzzle that every archaeological historian must complete in order to reconstruct and interpret the past while at the same time uncovering new sources to enrich our knowledge. The time spent by the archaeological historian in the field is in some ways equivalent to the time spent by a text historian in the archives. Both must then analyse and interpret their sources. These two stages of historical research are complementary and exciting.

Here are some illustrations when I work on the fortified works of the Greek cities that we have to inventory and describe on the field. The two photos were taken in Greece Argolid on the sites of the fortress of Kasarma and the small city of Ayios Andreas.

See also

Results of excavations in Cyprus

Updated le 22 December 2022